Spokester 1: Neural Game Graphics

I introduce Spokester1, a simple video game with a neural graphics engine. I train a video diffusion model from scratch on a single video that powers Spokester1's realistic graphics.

First draft: December 22, 2025

[github code] [youtube demo] [model weights]Welcome to the world of Spokester. In this world you play as Toni. You ride through the conjested streets of New York City pedalling your titanium fixie. Feel the wind rush by and hairs stand on end as you careen down a three lane boulevard.

There is only one objective: survive. How far can you make it before hitting a

car head on?

Toni

ToniGame Engine

Spokester1's underlying game engine has 700 lines of code. Toni is an unassuming cube. The sedans and buildings win no visual awards because they are also cubes. There are no animations, no keyframes, no cloth physics or lighting physics.

You start at a snail's pace and gradually accelerate until you are speeding like a maniac. The camera follows you with a slight delay. When you hit a car you come to an abrupt stop.

The game is fun and whimsical. But who wants to play a game with boring graphics? When I play Spokester1 I want to feel like I am Toni. I don't want to feel like I'm a green cube...

Neural Rendering

Like traditional games, Spokester1 separates the game logic from the rendering logic. This means we can swap out the rendering method with one that looks more realistic. A small army of artists could painstakingly craft detailed textures and meshes and skeletal animations. This takes a while and is expensive. But we are in the future! The AI can do all the rendering stuff for us!

The pixels that you see when you play Spokester1 are generated by a small

diffusion transformer. Far from being as compute hungry and expensive as many

SOTA models, Spokester1's neural renderer only has 100 million parameters and

costs $8 to train.

Dataset

Toni rides a lot. There are many hours of uncut 4K footage of his rides. Let's say we tell a 3D artist to fix Spokester1's graphics so that they match the style and realism of Toni's real videos. The artist would design 3D buildings and roads imitated from looking at the videos and try to tweak the lighting and colors so that it looks real. Neural rendering is similarly data-driven but sidesteps the intricacy of simulating the world in exact 3D detail. Neural rendering can shortcut lighting and texture by learning heuristics about how pixels in real videos look. Render a tree not by simulating every one of its leaves but by simply learning a heuristic tree blueprint.

I trained Spokester1's neural renderer on a single reference video. In this video Toni rides for 35 minutes through New York City in one continuous clip. They ride on busy highways and through tight intersections and over bridges and beneath skyscrapers. These 35 minutes portray an incredibly dynamic range of riding conditions.

Skip to random parts of the video and see how:- The camera follows Toni over the shoulder - just like in a video game.

- Terry keeps a consistent distance from Toni. He's mostly about 10 feet behind him.

- They weave between cars in multiple scenarios: gridlock, moving highways, empty streets

- Toni is constantly pedalling. He is riding a fixed gear after all.

Toni in the reference video

Toni in the reference video

Toni in the raw game engine

Toni in the raw game engineHow to prompt the neural renderer

Spokester1's game engine may lack fluff but it has some significant resemblance to the reference video. Both place Toni roughly in the center of the screen and show him moving forwards as cars rush by. Green cube Toni swerves side to side sorta like how real Toni does. Neural rendering doesn't need to invent forward motion and learn where to put speeding cars - this information is already modeled in the base game engine. Instead all the neural renderer needs to do is add some eye-candy to a given scene extracted by the game engine. This presents an intriguing distribution matching problem similar to neural style transfer. What signals can we exploit from the game engine that are similar in distribution to signals we can extract from the reference video, whilst being useful for generating the reference pixel values? In other words, how can we prompt the neural renderer?

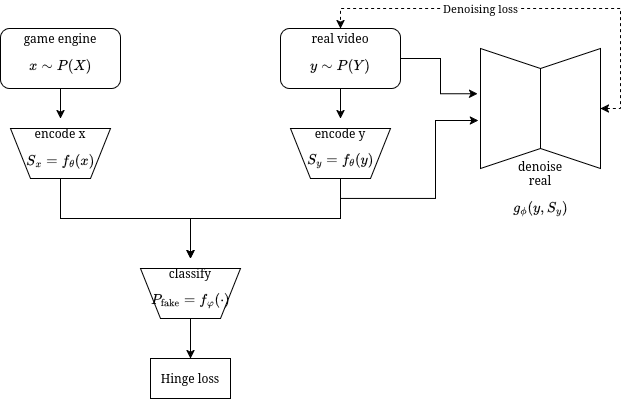

There are lots of complicated ways of approaching this dual distribution matching problem. There are GANs, DMD, and all sorts of regularization losses that can make a neural network generalize from information encoded from the reference condition to information encoded from the game engine. For example, if you were to employ a GAN loss, it would look something like this:

GAN loss for dual distribution encoder and denoiser

GAN loss for dual distribution encoder and denoiserIn this hypothetical setup, the encoder encodes both game pixels (x) and reference video pixels (y). The features from the real video (Sy) are used by the denoiser to denoise the real videos. The discriminator tries to distinguish between real features and fake features. The encoder tries to fool the discriminator by making the real and fake features occupy similar probability distributions, while also making the real features useful for the denoising task.

GANs are overly complicated and even just thinking about all the tangled up objectives makes my head hurt. I hope that one day the theory becomes simple and effective enough for engineers like me to employ. But for now there is a simpler way we can prompt the neural renderer.

The neural renderer only needs to add embelishment. The game engine already provides very rough 3D locations of big objects like Toni and cars. We can prompt the neural renderer with the game's 3D objects using a depth image for each frame. The game engine also already provides motion for Toni and the cars and the ground. We can additionally prompt the neural renderer with the game's underlying optical flow.

Just prompt with depth and optical flow

Every frame the diffusion transformer receives an optical flow map and depth map from the raw game engine.A single frame of optical flow is an image with the same height and width as the game's resolution but contains two channels (instead of the usual 3 RGB channels). Each pixel of the optical flow contains the instantaneous X velocity and instantaneous Y velocity relative to the camera. A single frame of depth is an image the same resolution as the game but only one channel. This contains the inverse distance from the camera to original point where the pixel comes from. Unlike in the game engine, there is no easy way to obtain the exact optical flow and depth of a real video. I use pre-trained neural networks to extract these from each frame of the reference. I use an off-the-shelf optical flow model and an off-the-shelf monocular depth model.

This simple architecture avoids the complexity of GANs and cross modal alignment. The diffusion transformer is trained to transform the reference's depth and optical flow into the reference's pixel values. It generalizes to transforming ANY depth and optical flow into pixel values that appear like the reference. This succeeds because the depth and optical flow do not inform the diffusion transformer of the exact colors and objects in the frames. For example, for a given depth and optical flow that show a moving car, the car's color could be red or green. It could be a jeep or a taxi cab. Since the flow and depth remove all the pretty details the model needs to come up with the eye-candy on its own.

Left: Depth and optical flow maps from the reference video.

Left: Depth and optical flow maps from the reference video. Right: Depth and optical flow maps from Spokester1's game engine.

Training the JiT / DiT model

Spokester's neural renderer is a depth and optical flow conditioned diffusion

model (DiT). I integrate the depth and optical flow information into the DiT

using patchification and subsequent AdaLN. I do not use a VAE and instead use

x-prediction

I add noise in the diffusion-forcing style, which means each framelet is noised with its own independent noise level. I use a shifted noise schedule that biases the timesteps to be more on the noisy end.

Before passing the depth and optical flow to the DiT, I normalize them based on a precomputed mean and std. So if the model sees a depth of 0.0, it means something of medium distance. A depth of -10.0 means something very close. With hindsight this decision was not the best and perhaps I should have used a log scale so that distant objects are easier to discern.

I use a ViT-B architecture with pinned AdaLN projections, resulting in a model with 100 million parameters. Even this small model quickly overfits to the single 35 minute reference video. This is not surprising. The model's weights are 200 megabytes while the entire 320x320 h264-encoded video is 263 megabytes. There are only 51 reference pixels for every model parameter.

Training-Inference misalignment

During training I monitor the denoising loss and iREPA loss, but also monitor the autoregressive (AR) reconstruction loss. The AR reconstruction loss measures the model's ability to reconstruct the exact pixel values of a clip from the reference video, given the ground truth optical flow and depth map. When deployed autoregressively the model must generate one framelet at a time and reuse a KV cache that it updates autoregressively. This is different from how the model is trained. During training the KV cache stores information from previous noisy framelets but during AR inference the KV cache stores information from noise-free framelets of the model's own creation.

I observed that the AR reconstruction loss decreased rapidly in early training but starts to increase as the model's internal representations become more sensitive. I tried modifying the timestep at which the KV cache is saved, decreasing this 'cache_at_step' index causes the KV cache to be stored for a token when it is more noisy. A 'cache_at_step' of around 50% of the number of denoising improved the AR reconstruction loss.

The lowest AR reconstruction loss is reached by caching KV at step 10 / 20 denoising

steps. AR reconstruction loss measured on a single 256-frame clip.

The lowest AR reconstruction loss is reached by caching KV at step 10 / 20 denoising

steps. AR reconstruction loss measured on a single 256-frame clip.It works!

Even after only a couple thousand steps of training, the model learns to successfully hallucinate a real looking Toni where the green cube Toni was. Motion and details seem to take longer to learn. I'm proud to show off my Spokester1 neural rendering model trained for 250k steps.

Try to look out for these cool details I noticed. Toni's shirt seems to flutter in the wind! This looks really cool and is kinda subtle. Toni's shadow looks realistic. It adopts to the steering angle and his position on the road. As he passes behind buildings he is shaded. Riding out into an intersection he is lit brightly.

Issues and shortcomings

Everything is blurry and grainy. The visual horizon degrades into a huge tunnel-like hole. Steer too fast and you risk conjuring up hallucinated cars that aren't in the game.

If you steer really abruptly side to side the game perceptually speeds up! This looks really trippy. I suspect this is due to some sensitivity to the magnitude of the optical flow, large flows are only really seen when the video is going really fast.

If the camera clips through a car the whole screen goes beserk. This is not something that happens in real life so how would you expect the neural renderer to fly through a car. But the extreme artifacting is probably from the depth values being very small and overflowing.

Despite training the model on clips of up to 256 frames, the best settings for inference use only 6 frames and a sliding KV window. This indicates that long context understanding is difficult to directly apply during autoregressive inference. Some sort of post training could solve this but is beyond the scope of Spokester1.

Play it yourself!

Spokester1 can run at 30fps on a gaming gpu. Checkout the github page for more information.